Heart Bound in Armor: An Appreciation of Sir Frank Dicksee's Work

Courtly Love, the Chivalric Ideal, and Doomed Romance in Dicksee's Work

The first time I came across Sir Frank Dicksee’s painting Romeo and Juliet, I immediately felt a pang of disappointment, wishing medieval art actually looked like this (sadly, depth wasn’t a thing in 12th-century art). As I delved deeper into his work, I discovered that his paintings draw their very essence from medieval courtly love, also known as Fin’amor. Today is going to be a little different, as I want to share my small analysis of Dicksee’s work and how we can see the influence of medieval literature in it.

Sir Frank Dicksee (1853-1928) was born into a family of artists, and by age 16, he was already excelling at the Royal Academy, where he developed a romantic, richly colored style. Though he wasn’t officially part of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, his work share its dreamy, historical and mythological spirit.

Courtly love, which emerged in the 12th century, served as a cultural shift where love began to be expressed as a performance (just imagine Romeo under that balcony). At the heart of medieval literature, this movement transgressed feudal norms, especially those surrounding forced marriage and marital submission. Lovers defied these conventions, marking the beginning of the romanticization of adulterous love.

The Chivalric Ideal

Often depicted as the son of a nobleman, the knight is the hero and protagonist of courtly literature. He embodies bravery and righteousness, submissive to his king while performing great military feats. This relationship of domination between a knight and his lord, is transposed into love.

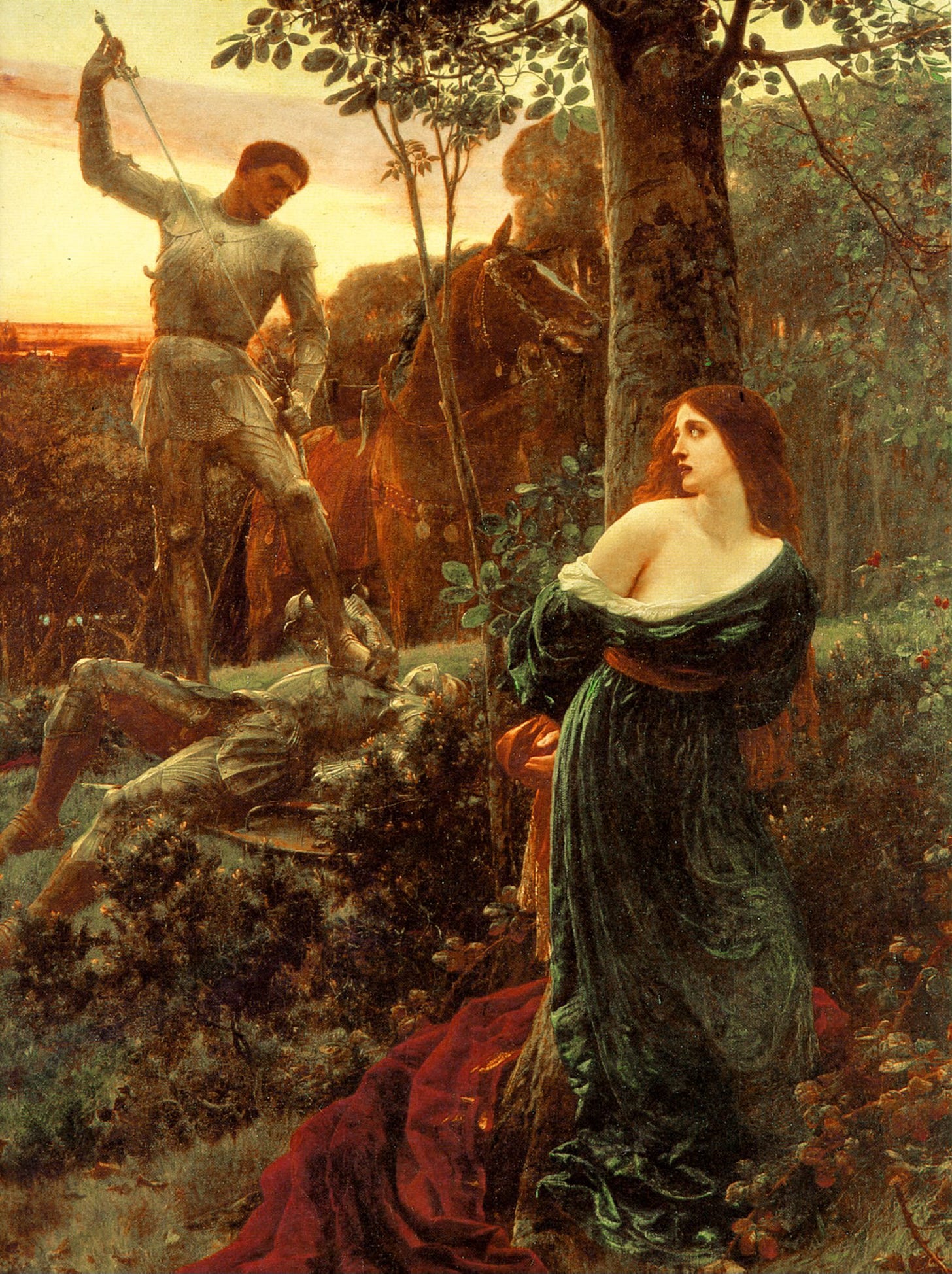

In his painting Chivalry, Dicksee illustrates Sir Galahad, the son of the knight Lancelot, an important character from courtly literature, saving a damsel in distress. Galahad is depicted putting his sword back into its sheath after killing a wicked knight.

Doomed Romance

Courtly love is far from happy; it is socially unacceptable and often leads both lovers to a tragic end, like that of Romeo and Juliet. (Although Shakespeare comes much later, his story captures the same essence of medieval courtly love.) The same is true for Paolo and Francesca. , whose lovers, trapped in family rivalry, embody a doomed, adulterous love that defies societal norms. They experience an impossible relationship marked by shame and secrecy, adding to the tragedy of their fate.

A Woman of Ice

Despite the fact that love is a central theme of courtly love, it is important to understand that this love represents more of a form of one sided submissive affection. Once struck by Cupid's arrow, the knight becomes a slave to his own heart, losing all control and rationality over his actions, willing to cheat, kill or even die for the chance to experience this love. While an emotional fever torments him relentlessly, he musters the courage to declare his passion to the lady.

In An Offering, we see a woman lifted on a confortable chair, clearly in a position of suportiry, hardly acknowledging the man behind her who is despetly trying to gain her attention. The man holds a figurine of an angel in his hand, a cherub kneeling with its head bowed before the woman, symbolizing his romantic submission. In response to that offering, the woman appears merely amused. Another detail that I’ve noticed in the painting, if you look at her right hand, what do you see on her ring finger ? Yes, a ring! This painting perfectly embodies the adulterous nature of courtly love.

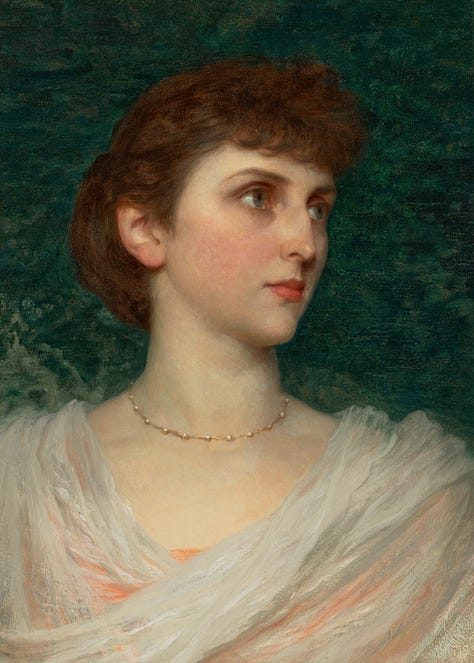

In the portraits of Sir Frank Dicksee, women often appear as icons of beauty and pride, embodying the very essence of the female from medieval romances. With their chins held high, they display an almost cold dignity…

Romantic Disillusionment

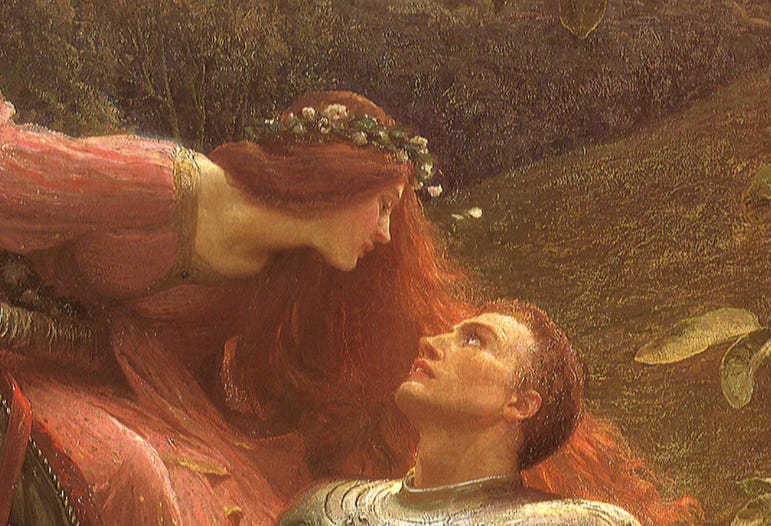

This painting is the story of La Belle Dame sans Merci, inspired by the poem by John Keats, en s’inspirant d’un récit d’Alain Chartier, écrivain du Moyen-Âge. The title says it all, it’s about a beautiful lady without mercy.

In this painting, we see a knight, normally meant to embody strength and courage, who is found in a state of complete fascination as he looks up, slimly leaning backward, as if hypnotized by the beautiful woman. Faced with her beauty, he becomes a prisoner of her gaze, revealing the fragility of heroism in the face of passion and love.

Thus, here comes one final characteristic of courtly love: the mythical nature of the woman, who is sometimes illustrated as a magical creature that appears in the knight's quest to guide or enchant him, sometimes with the intent to make him suffer. Do the names Vivianne or Morgana ring a bell?

In the poem, after this encounter, the man falls asleep before this enchanting woman, only to awaken alone, cold, and plunging into profound disillusionment as he realizes the impossibility of loving a being who may not even be human, or may not exist at all.

[…]

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful, a faery's child;

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sideways would she lean, and sing

A faery’s song.And there we slumber'd on the moss,

And there I dream'd, ah woe betide!—

The latest dream I ever dream'd

On the cold hill side.I saw pale kings, and princes too,

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all;

Who cry'd—'La Belle Dame sans Merci

Hath thee in thrall!'And this is why I sojourn here,

Alone and palely loitering,

Though the sedge is withered from the lake,

And no birds sing.-La Belle Dame Sans Merci (1819)

Really enjoying your posts 😀🖌️

honestly, bring back chivalry and courtly love idc the consequences 🙄